The Battle of Prestonpans

The Battle of Prestonpans was the most defining Jacobite victory in the final uprising of 1745-6. Support for Jacobitism had waned over the years and never fully manifested at the correct time for the Catholic Stuart cause. After many failed attempts at uprisings under the Old Pretender, King James VIII and II, many were wary of fighting for a rebellion that had seen multiple failures due to disorganisation, conflicting political interests, and lack of manpower and arms in comparison to the British Government.

Support from France was an absolute necessity to the Highland Jacobites, who were heavily outnumbered by British Government forces. Yet France’s support was not always reliable - often being preoccupied with its own problems with war against Britain, and a need for peace to stabilise the French economy. The Jacobites desperately required a victory to boost morale and catch the attention of the Catholic European powers.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, also known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, or The Young Pretender, had launched the Jacobites into rebellion on the 19th of August, 1745, at Glenfinnan in the Scottish Highlands. Dissatisfaction with the Union had been brewing in Scotland since the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1719. Many Scots resented the Union for the loss of political and economic control they faced, seeing little economic gain in return. The Highlands still remained largely underdeveloped, and incidents like the malt tax riots in 1725 saw uproar from Scots across the country due to the extension of English taxes to Scotland. As France began to set its sight on a Stuart restoration in Scotland once more, and Bonnie Prince Charlie successfully rallied the Highland troops to his side, the time was finally right for another Jacobite rebellion.

Whilst they never held Edinburgh Castle, Charles and his Jacobite army successfully took Edinburgh on the 17th of September, 1745. For six weeks, Charles and his Highlanders held the capital. They proclaimed him King the next day, and set up court in Holyrood Palace, where Charles’s Stewart ancestors had resided for centuries beforehand.

The Jacobites had narrowly beaten the British Government commander, Sir John Cope, to Edinburgh. He and his troops had sailed for Dunbar, East Lothian, but Charles and the Jacobites had already taken the city that morning. Cope disembarked his men in Dunbar and prepared for battle, still feeling confident - he held an army of 3000-4000, compared to the poorly armed 2000 of the Jacobites. However, many of his men were poorly trained, with no battle experience. Charles led his army eastwards into East Lothian, and the two met in Prestonpans on the 20th of September.

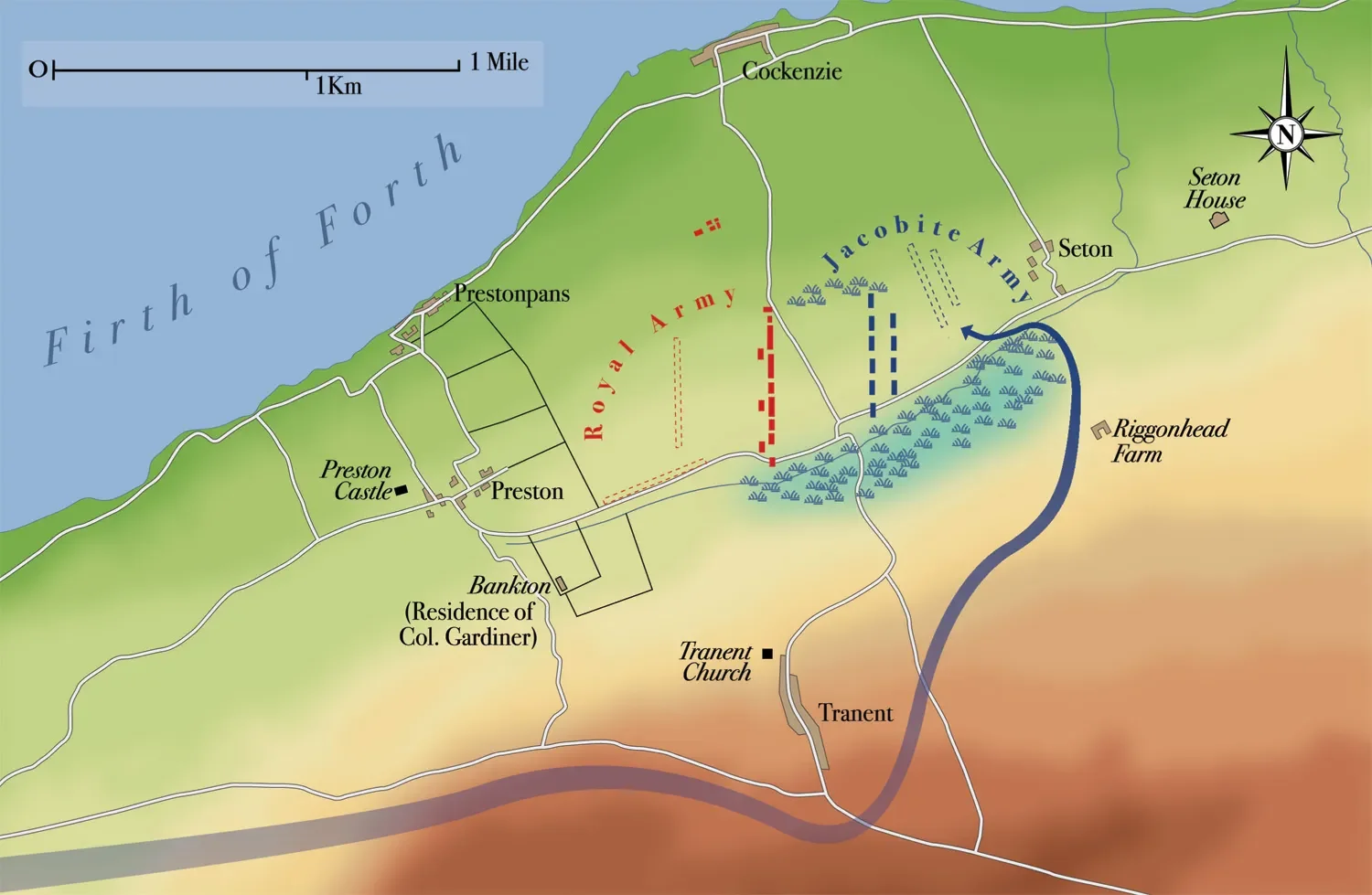

Cope initially set up his army facing southwards, with the marshy terrain in front of their lines. Charles sought an immediate attack on the British defences, but Lord George Murray, a senior commanding officer of the Jacobites, advised against this action. An immediate attack would have been detrimental to Charles’s army due to the marshy terrain, which would expose them to the superior firepower of Cope’s army. Whilst this was true, and Charles heeded the advice, it marked the first of many internal disputes within the Jacobite command that would continue until the end at Culloden.

Murray argued that a surprise attack was the best route to victory, as Cope’s left flank remained open and vulnerable. A local farmer’s boy, Robert Anderson, provided intel on the landscape and offered a route that the Jacobites could take through the marshlands. By 4am, they were slowly and stealthily moving to Cope’s east, preparing for attack.

Cope had soldiers on watch throughout the night to prepare for surprise attacks, who warned him of the oncoming Jacobites. He managed to turn his army around to face eastwards and fight back. However, his two dragoons on the flanks fled the scene once the Jacobites appeared, making the British infantry much easier to attack. Within minutes, British defences were shattered and overrun. The battle was won in under half an hour.

The layout of the battlefield meant that retreat had not been an option for the British troops - park walls blockaded them in. This meant that around 500-600 were captured by the Jacobites. Total figures are estimated as:

Government - 300-500 killed, 500-600 captured

Jacobites - 35-40 killed, 70-80 wounded

Only a few hours after the battle, Cope had fled the field with over 400 survivors to Berwick-Upon-Tweed. He wrote of his defeat, “I cannot reproach myself; the manner in which the enemy came on was quicker than can be described... and the cause of our men taking on a destructive panic” (Wemyss 276).

Whilst it was decided by the court that the British defeat was due to the conduct of his troops, Cope never held a senior command again. His defeat is immortalised by Scots through the folk song, “Hey, Johnnie Cope, are Ye Walking Yet?”, which satirises his defeat in Prestonpans. The lyrics were written by a local farmer, Adam Skirving, who visited the battlefield that afternoon. He also wrote the song “Tranent Muir”, but “Hey, Johnnie Cope” became the popular tune most associated with the battle. Robert Burns would also later write his own lyrics to the song, though they are not as well known as Skirving’s. Whilst the song celebrates the victory, its satire largely exaggerates the happenings of the battle and is not exactly accurate to real events. The chorus is as follows:

Hey! Johnnie Cope are ye waukin' yet?

Or are your drums a-beating yet?

If ye were waukin' I wad wait,

Tae gang tae the coals in the morning.

Prestonpans was a devastating and embarrassing loss for the Government, and an invaluable win for the Jacobites. It boosted morale for the Stuart cause, and solidified it as a real rebellion and true threat to the British Government. By October, French ships sailed for Scotland bringing money and arms to aid the cause.

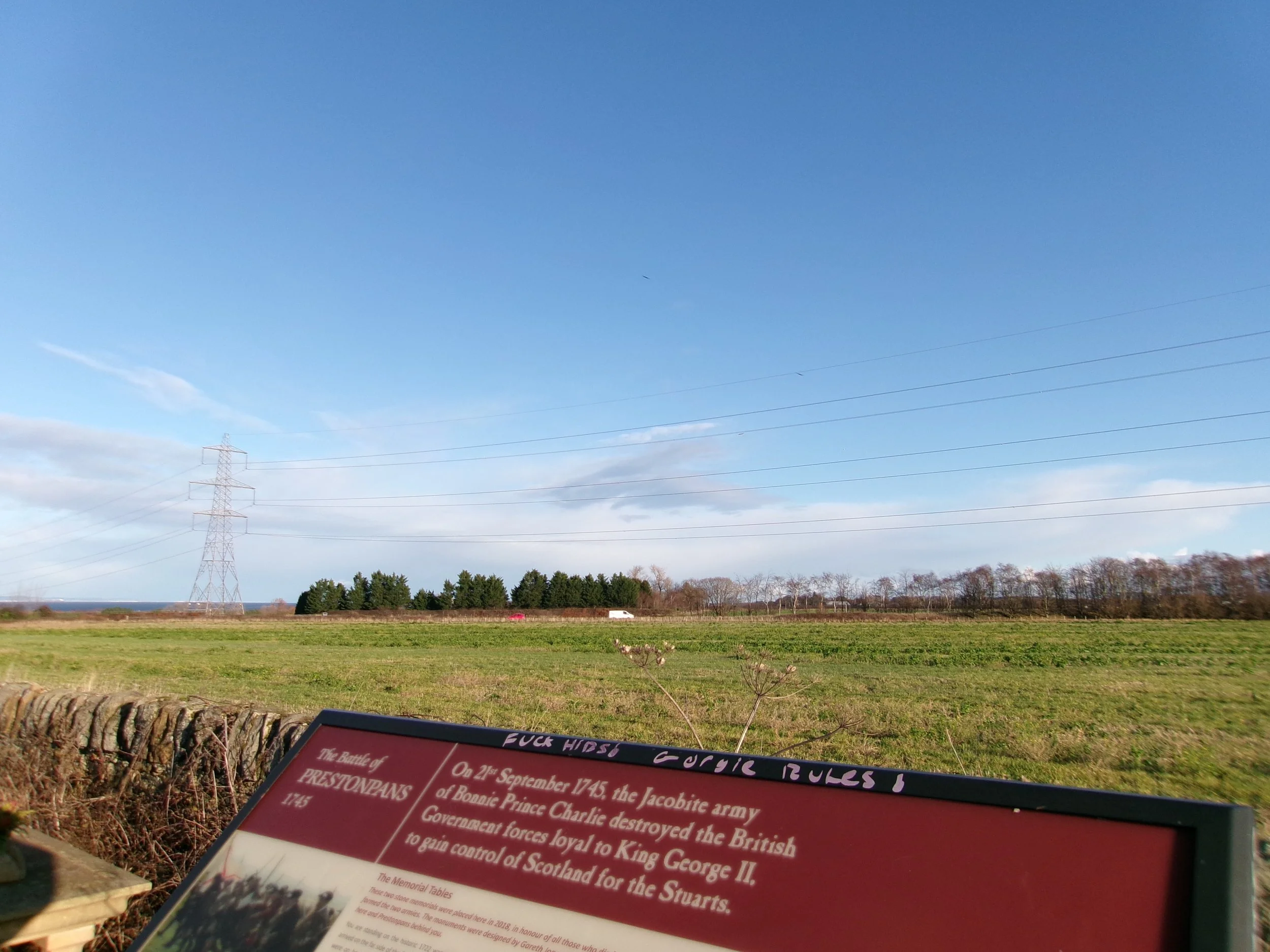

Whilst the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-6 resulted in failure at Culloden, the Battle of Prestonpans is still remembered as a fine victory for the Jacobites. In Prestonpans today, there is a walking trail including monuments and the battlefield that can be walked in an hour. The battle is still a source of pride to locals and Highlanders alike, and continues to be memorialised through such songs, stories, and historical sites.

References

The Battle of Prestonpans (1745) Heritage Trust. Available from: https://www.battleofprestonpans1745.org/

Wemyss, David. A Short Account of the Affairs of Scotland: In The Years 1744, 1745, 1746. Edinburgh: David Douglas. p.276