A Burns Night for All

Scotland's national bard is one known throughout the world for his passionate poetry, working class lifestyle, and tumultuous romances. The life of Robert Burns is celebrated in Scotland on every 25th of January by patriots and poetry lovers alike. Scots across the nation are taught to read and recite the poet's work from an early age, but whether you are an avid reader, or in need of a refresh, here's a wee background of the poet that will help you understand just what makes him so special to us Scots.

Robert Burns (known colloquially in Scotland as "Rabbie" Burns) was born on the 25th of January, 1759, in Ayrshire on the west coast of the Scottish Lowlands. He lived his life as a humble farmer, often facing hardships like poverty and bankruptcy as his father struggled with debt.

Burns began to develop as a poet throughout his early life, and published his first book of poetic works, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, in 1786. This was an immediate success, and catapulted him from a humble Ayrshire farmer, into a captivating poet who impressed the Edinburgh gentry by proudly showcasing his agricultural roots. In a world where poets wrote about the natural world, describing it in fanciful terms as they travelled and explored, Burns actually lived it. Authenticity bleeds through the page as you feel his hardships, which are not idealistic portrayals of countryside living, but physically grounded experiences.

He was a free-spirited man, which was often reflected in his poetry. Poems like ‘Tam O Shanter' surged in popularity for their brutally honest portrayal of the working man's lifestyle.

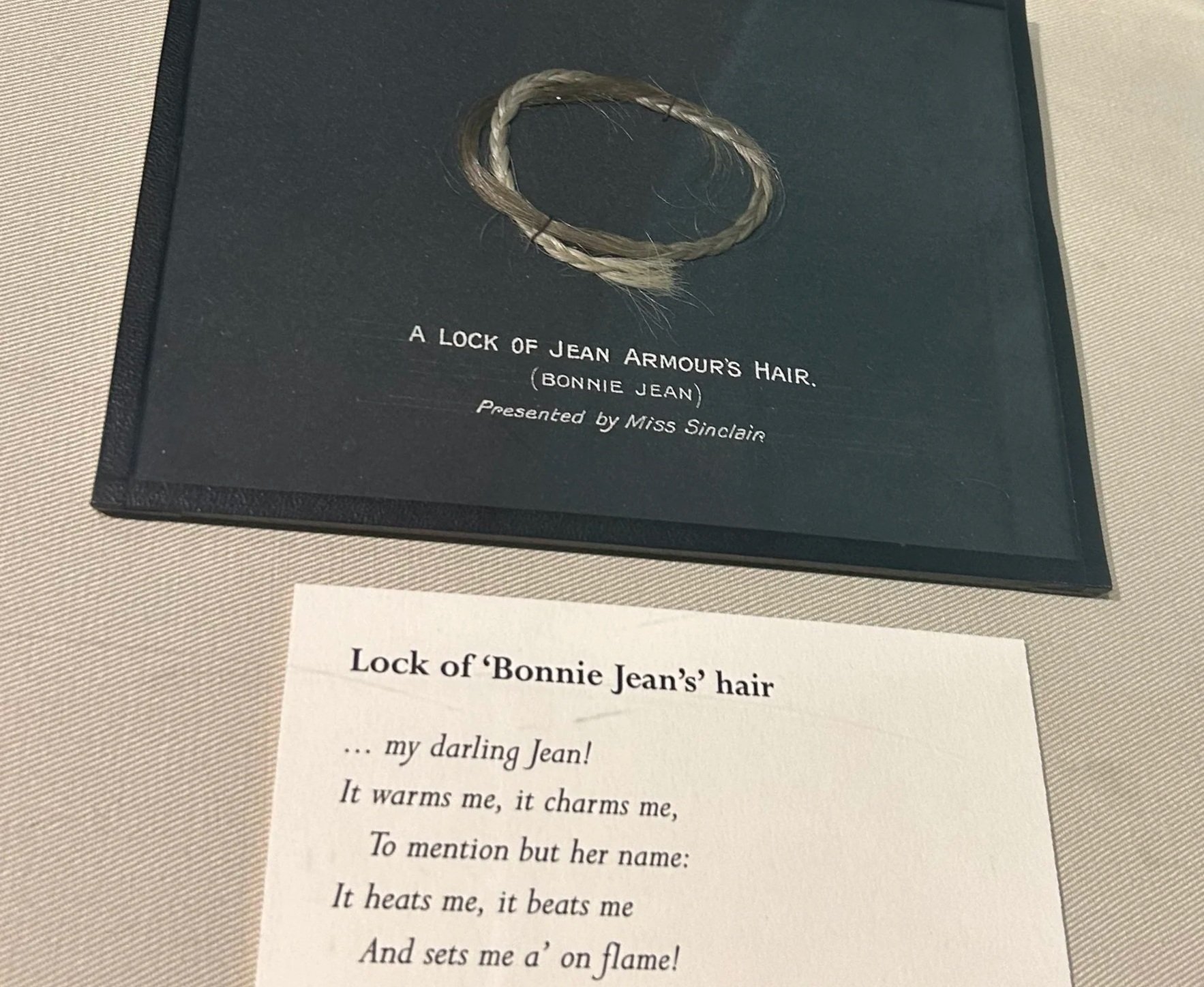

His romantic works were beautiful odes to many of the women in his life (he was a notorious womaniser), with works like 'My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose and 'O Were My Love Yon Lilac Fair’ providing poignant lyricism that still resonates today. He was a man unafraid of depicting his lower moments; his emotions are not elevated and idealised, but grounded in the moment. He is honest and conversational - traits perfectly expressed on the page through the Scots language, which makes it sound almost spoken rather than written.

These qualities have seen the bard celebrated in Scotland for centuries. Celebration comes in many forms, but will always include consumption of our traditional food: haggis, neeps, and tatties.

Haggis was a staple of the Scottish diet in the time of Burns; cheap to produce, this dish provided a source of sustenance during a period of economic hardship, whilst still retaining a delicious flavour. Burns celebrates it in his ‘Address to a Haggis’, comparing the humble haggis with more refined and decadent international dishes, and humorously portraying it as the greatest of all meals.

Great chieftain o’ the pudding-race!

Aboon them a’ ye tak your place

Burns Night celebrations are often accompanied by a rendition of ‘Address to a Haggis’, as the haggis is sliced open and prepared to eat. This can be read by either host or guest, so long as they bring an enormous amount of enthusiasm to the grand performance.

Who you celebrate this special night with is a matter entirely up to yourself. Many families celebrate at dinner time with the traditional meal. Friends often share a drink together at their own gatherings. During my time at university, many held their own Burns Night parties to dine together and recite a word or two. Many establishments will often host Burns events, including elements of traditional Burns celebrations like suppers, poetry readings, whisky tastings, and ceilidhs.

Across Scotland there are over 100 Burns clubs (Bonar, BBC). These are groups who celebrate the life and work of Robert Burns by hosting their own events within their local towns or districts. They often have a long night of Burns-centred fun, including feasting, drinking, poetry and singing, bagpipes, toasts, and competitions.

Burns clubs are more formal events, and are often structured to celebrate in these various ways throughout the night. They are usually run by a committee and headed by a chairman who ensures the event runs smoothly. The night usually has a dress code that adheres to traditional Scottish dress. For gents, the kilt and Argyll jacket is the most traditional, but dress trousers are also an option. For the lasses, smart skirts or dresses are common, with a tartan sash often applied to elevate the look.

They are often members-only events, aside from a select few guests. Historically, membership for Burns clubs has been strictly male only. Burns clubs have had a long history of male-dominance since their origins in 1801. What began as nineteenth century ‘boy’s clubs’, spaces of drinking and debate (activities in which no respectable woman would dare partake in), soon became tradition. Rules were gradually established that assumed male only membership, weaponising “tradition” as a means of formally excluding women from the fun.

And so it continued for years onwards. In their Burns clubs, men could be bawdy, drunk, and philosophical - everything women could not be. And so Burns was framed as a “man’s poet”; his drinking, his patriotism, his womanising were all celebrated as a masculine poetic performance.

But Burns was, in fact, far more progressive in his writings on women than could be assumed. He was a critic of all hierarchies - his aversion to inherited rank applies just as much to gender as it does class. In Burns’s poetry, women speak, judge, argue, feel, desire. He wrote them as he saw them, not passive objects to be toasted to but never listened to, but as real, living beings with agency.

A particular favourite few lines of Burns come to mind when discussing his thoughts on women. In ‘The Rights of Women’, he writes:

While Europe's eye is fix'd on mighty things,

The fate of Empires and the fall of Kings;

While quacks of State must each produce his plan,

And even children lisp the Rights of Man;

Amid this mighty fuss just let me mention,

The Rights of Woman merit some attention.

In typical Burnsian fashion, the poet flips an established idea on its head, and pokes holes in its logic. As society began to discuss Enlightenment ideals throughout his time, debating freedom, liberty, and rights, Burns playfully suggests these also be applied to women.

Burns was no Wollstonecraft; this is not a political manifesto arguing for real reform by breaking down any systems. Instead it’s a ridicule of men who expect submission from women, without considering their own autonomy and choice. Burns is not the first to come to mind in concerns of feminist activism, but he did clearly hold the belief that women deserved to be heard and respected. Yet in Burns club culture, they were excluded and denied a voice for centuries - undercutting Burns’ real values.

Thankfully in recent times, real change is happening. As gender roles have progressed over time, the male-dominated grip over membership has gradually lessened, and women are now seen in many clubs. Ladies have also formed their own Burns clubs, like the ‘Irvine Lasses’, established in 1975.

I myself attended a Burns club event, hosted by the Tranent Burns Club, only last year. I happened to get chatting to the committee members about a month beforehand at my old job, after overhearing them mentioning the Bard’s name. I told them about my interest in Burns and my degree in literature, we exchanged details, and I was formally invited to attend with a guest of my choice.

This was fortunate timing, as 2025 happened to be the first year in its history that the club was allowing female entry to the event.

It was a night of structured fun. The ‘Address to a Haggis’ was performed exquisitely, the young piper did fantastically well and was greatly applauded. We ate hearty meals and had lots to drink. The poetry readings were frequent and impressive throughout the night, and we concluded with a rendition of ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

I counted around five or six women amongst over 50 men - a small start to what I hope will be a growing number in time. One of us women was, in fact, a speaker and singer at the event. She was the daughter in a family of male club members, and she had been excluded for years up until this point. She spoke confidently about how her knowledge had actually exceeded them all since she was a girl, but the exclusion of females had meant that she remained at home whilst her male family members were allowed to celebrate with the club. Over the years she had protested in various ways (one memorable one being a stink bomb at a club meeting), until she and us other women were allowed entry. It was a rousing speech for myself and my female friend I had brought along, and we cheered her loudly afterwards.

The Burns club supper was an experience I’ll never forget. As women are gradually forcing their voices to be heard in Burns clubs, they have been opened up to a new form of celebration of Burns. These communal spaces should be shared between the sexes, because love for the Bard is not felt solely from just one of them, but both, equally.

Many Burns clubs are struggling with declining numbers and a lack of participation from the youth. Ageing membership is a serious problem when the youth aren’t interested in keeping the clubs alive. By expanding beyond the narrow demographic they previously allowed, Burns clubs can thrive and not just survive.

Celebrating the Bard is an activity that can be solo or shared. Burns was never a poet who should have been frozen in tradition, but one whose work is progressive, open, and experienced. Celebrate in a way that aligns with his values - with pleasure, with emotion, and without hierarchy.

Works cited

Bonar, Megan. ‘I was told I was too glamorous to do a good Burns speech’. BBC Scotland News. 25 January 2024. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-68020589